for adopting a single-clef system

As mentioned in the introduction, the goal of this document is to end the current use of F-clefs and C-clefs in music notation. When mentioning this to people, I get very different reactions. Many agree with me, but most people say it is impossible. And, funnily enough, a few get angry. I owe a big thank you to a guy at the Norwegian Academy of Music. He actually frightened me with his anger, even though it was only a phone call.

This incident triggered my crusade. When well-educated adults react like he did, I know I am onto something. On the other hand, several educated and experienced musicians agree with me and support my cause, and this is of course another strength for me. I don’t believe that my ideas will come through in just a few years; I am only trying to speed up a process that has gone on for a long time. Perhaps we’ll be there in a generation or two.

The use of all these different clefs began hundreds of years ago. The system was probably fine for choir singers back then. Our current situation began when “proper” composers started making music for all sorts of instruments, and just adopted the system of staffs and clefs from their ancestors. Flutes got a notation similar to sopranos, and instruments that rumbled in the lower registers got a system similar to the bass singer. In a time when paper was expensive, it was smart to put as many staffs as possible on a page. And it was also, for a well trained composer, quicker to use a lot of different clefs instead of writing ledger lines.

The midrange instruments had to keep up with different alto and tenor clefs, as best they could. The composers were in charge, and musicians had no choice but to learn to understand what was written. And this has gone on until now. Music history is not my strongest point, and those who find this important will have to look elsewhere for more information. But I can clearly see how silly music notation is today, and the serious consequences this has for music as a whole. This applies to amateurs and professionals alike.

I will now present my arguments for using a music notation based solely on the treble clef. These arguments are written paragraph by paragraph, in no particular order.

Most musicians today are using instruments where the music is written in the treble clef. Therefore, I find it natural to choose the treble clef as the one and only clef in future music notation.

Learning to read notes can be compared to learning how to drive a car. Almost everyone start off with the treble clef when learning to play music. This becomes like seeing forward. You walk forward, you drive forward, and so on. Trouble begins the day the piano teacher gives you a sheet with the grand staff, both treble and bass clef on the same page. Now you have to drive backwards, just by using the rear-view mirror. You can manage at slow speed, but it is impossible to do it as precise and as fast as driving forward. The result is that you quit playing. Most people who quit playing the piano say it is because of the bass clef. And this is, quite frankly, tragic. I know several persons with great aptitude for music, but playing the piano? No thanks, they have better things to do.

When reading notes, visual pattern recognition is extremely important. It can take years to sight-read just one clef efficiently, and learning another clef just complicates and prolongs this process. Simply understanding a clef has no value, you have to be able to read and translate it at full speed. This takes a lot of practise and a lot of time.

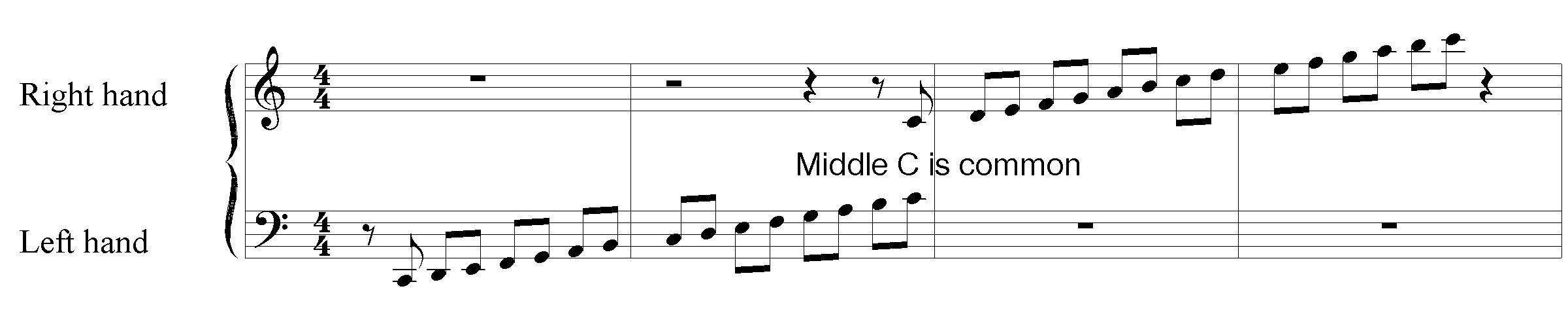

Simply put, the traditional grand staff consists of an upper staff written in the treble clef, and a lower staff written in the bass clef. There is only one ledger line between them, the middle C. The following example shows piano notes written in the old grand staff:

In my music notation system I have replaced the bass clef with another treble clef, which requires two ledger lines between the two staffs. Brilliant! The following example shows the same piano notes, written in my notation:

(I could have written G4 in front of the upper staff and G2 in front of the lower, to specify which octaves should be played. In my opinion, this is uneccessary because of the natural placement of your left and right hand when playing piano notes.)

Most people who find the current musical notation to be just fine, and probably never questioned it at all, are professional musicians who have studied for six or eight years. They are unable to see that others may have trouble understanding or learning what has become second nature to them, just like we all do when we know something well. They seem to forget that most musicians in the world are, and will forever be, amateurs. Among these amateurs there are, proven beyond a doubt, some who outperform most professional musicians. And many of these amateurs can not read a single note.

If my wish comes through, learning music notation will be a lot easier. That has to mean something, even for highly educated music professors. Or maybe they are afraid that music studies might take a year or two less? Why the reluctance to replacing F- and C-clefs with the treble clef? Because all sheet music printed so far use these relics? That is not an argument. Everyone able to read and play different clefs may feel free to do so until they die. But we have to stop wasting the time of new generations by teaching them unneccessary clefs.

Publishers will most certainly embrace the opportunity to print new editions, and the transition to an improved music notation will be painless. An incredible amount of new technologies have seen the light of day these last hundred years, and many “wise” men have judged these inventions as useless amusements with no practical value. Some years ago, Sweden managed to go from left lane driving to right lane driving, and the United Kingdom finally adopted the metric system. Nothing is impossible. Notating music using only one clef is not a revolution, it’s just an adjustment. Cross-head screws are a fairly new invention, but they have already been replaced by TORX screws in many applications. I can’t imagine anyone protesting better grip and less cam out just because they have some old screwdrivers lying around that they want to use!

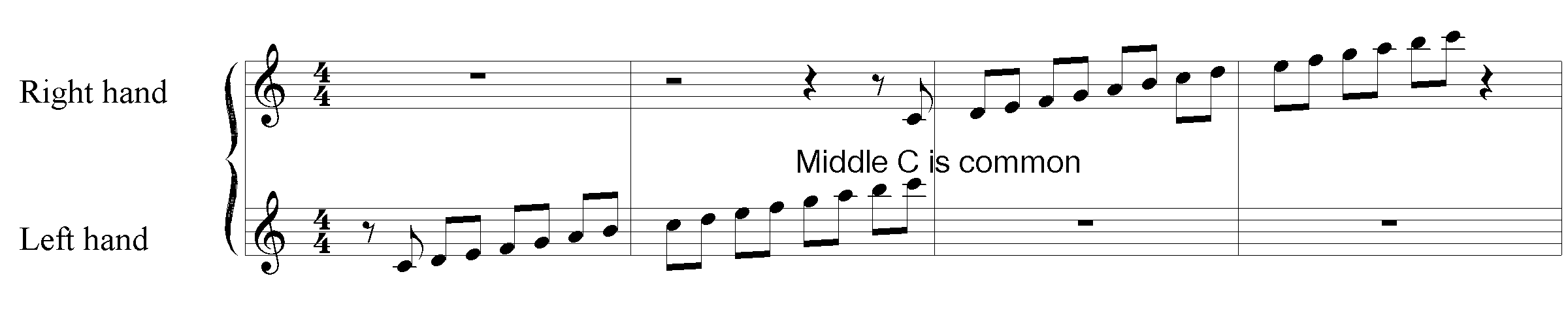

A simplified music notation system based on the treble clef will be a huge step towards what is important; giving as many people as possible access to the wonderful world of music. Not only as an audience, but as musicians themselves. Playing music, alone or with others, is such an important part of life. Let’s not deny so many this experience just because of this old fashioned, cumbersome way of writing music. These two examples show the same organ melody. It seems obvious that the second example, using only the treble clef, will be much easier to learn than the traditional system.

A popular argument against a single clef system is that it is important to show exactly what pitch a note represents. Is it the middle C, high C, or what? But for a musician this isn’t important at all. People using this argument don’t realize that there are just as many “incorrectly” notated notes as there are “correctly” notated notes, without it causing problems for a single musician. All a musician needs to know is how, in practise, a transposing instrument can play together with a non-transposing instrument. And all a composer needs to know is what pitch range each instrument has, in order to make good harmonies.

Notes written for A, Bb, C and Eb clarinets all use the treble clef. But only the C clarinet is “correctly” notated, according to those that say we still need both the treble and bass clefs. In other words, normal practise has long ago killed the “correct” notation.

The clarinet can serve as an example to show how it is possible to use a notation similar to the treble clef for all instruments. Imagine the note corresponding to the middle C in the treble clef. All clarinets use the same fingering to play this tone, C4, the lowest playable C in a clarinet’s range. (Except some bass clarinets that play one octave lower, most clarinets cannot play lower than E3.) This system can easily be copied to all other instruments; the visual “middle C” on the staff is the lowest C in the instrument’s range. With some exceptions, of course. The flute and piccolo, for instance, should have their notation moved down one more octave. This way, their most used notes will be written within the regular staff lines, and not several ledger lines above.

I have often used the piccolo as an example in discussions. If bass instruments need a bass clef to avoid too many ledger lines, then it’s obvious that the piccolo also needs its own “supertreble” clef. Boy, does that instrument use many ledger lines! Funny story from my phone conversation with the angry fellow at the Norwegian Academy of Music; he actually tried using the piccolo as an example of why I was wrong, but he quickly realized his error. In his own words: “…uh, allright, the piccolo is already written in the treble clef, but, but… uh, how about the double bass? How do you think its sheet music would look if it was written using the treble clef?” Well, pretty tidy, actually. I have made a small example sheet further down.

“Handy Manual Fingering Charts for Instrumentalists”, published by Carl Fisher, is a clever little booklet that I highly recommend buying. I have made a list of all instruments mentioned in the booklet, with comments regarding their notation in the booklet:

- C piccolo is notated one octave too low.

- Db piccolo is notated one octave too low.

- C flute is correctly notated.

- Oboe is correctly notated. (But I think all flutes should be notated one octave lower.)

- English horn is correctly notated.

- Bb clarinet is correctly notated.

- Alto clarinet is correctly notated, by my standards, but sounds one octave lower.

- Bb bass clarinet is correctly notated, by my standards, but sounds one octave lower. (In Europe both the treble and bass clef is used for bass clarinet notes.)

- Bassoon is correctly notated, but uses the bass clef.

- Contrabassoon is notated one octave too high, and uses the bass clef.

- Bb trumpet is correctly notated, by my standards.

- Cornet is correctly notated, by my standards. (Similar to the trumpet.)

- Alto horn is notated one octave too high. (Visually similar to the trumpet.)

- Baritone horn is notated two octaves too high. (Visually similar to the trumpet.)

- French horn is correctly notated, but could be notated one octave higher. Some fingering charts use only the treble clef, but others use the bass clef as well. (F instrument.)

- Trombone is correctly notated, but uses the bass clef. (The trombone is really a Bb instrument, but is called a C instrument in the bass clef.)

- Baritone is correctly notated, but uses the bass clef. (It is also called a C instrument, and therefore has different fingering than if it was called a Bb instrument.)

- Eb tuba is correctly notated, but uses the bass clef. (It is also called a C instrument. In Europe the tuba is an Eb instrument, and uses the treble clef.)

- Bb-tuba is correctly notated, but uses the bass clef. (It is also called a C instrument.)

- Eb alto saxophone is correctly notated, by my standards.

- Bb tenor saxophone is correctly notated, by my standards, but sounds an octave lower.

- Eb baritone saxophone is correctly notated, by my standards, but sounds an octave lower than the alto saxophone.

- Xylophone is correctly notated.

- Marimba is correctly notated.

- Chimes are correctly notated, but sound an 8va lower.

- Bells are correctly notated, by my standards, but sound two octaves higher.

- Violin is correctly notated.

- Viola is correctly notated, but sometimes uses the C clef.

- Cello is correctly notated, but also uses the bass and C clefs.

- Double bass is correctly notated, but uses the bass clef and sounds an octave lower.

- Harp is correctly notated, but also uses the bass clef.

- Celesta correctly notated, by my standards, but also uses the bass clef and sounds one octave higher in both.

- Orchestra bells are correctly notated, by my standards, but sound two octaves higher.

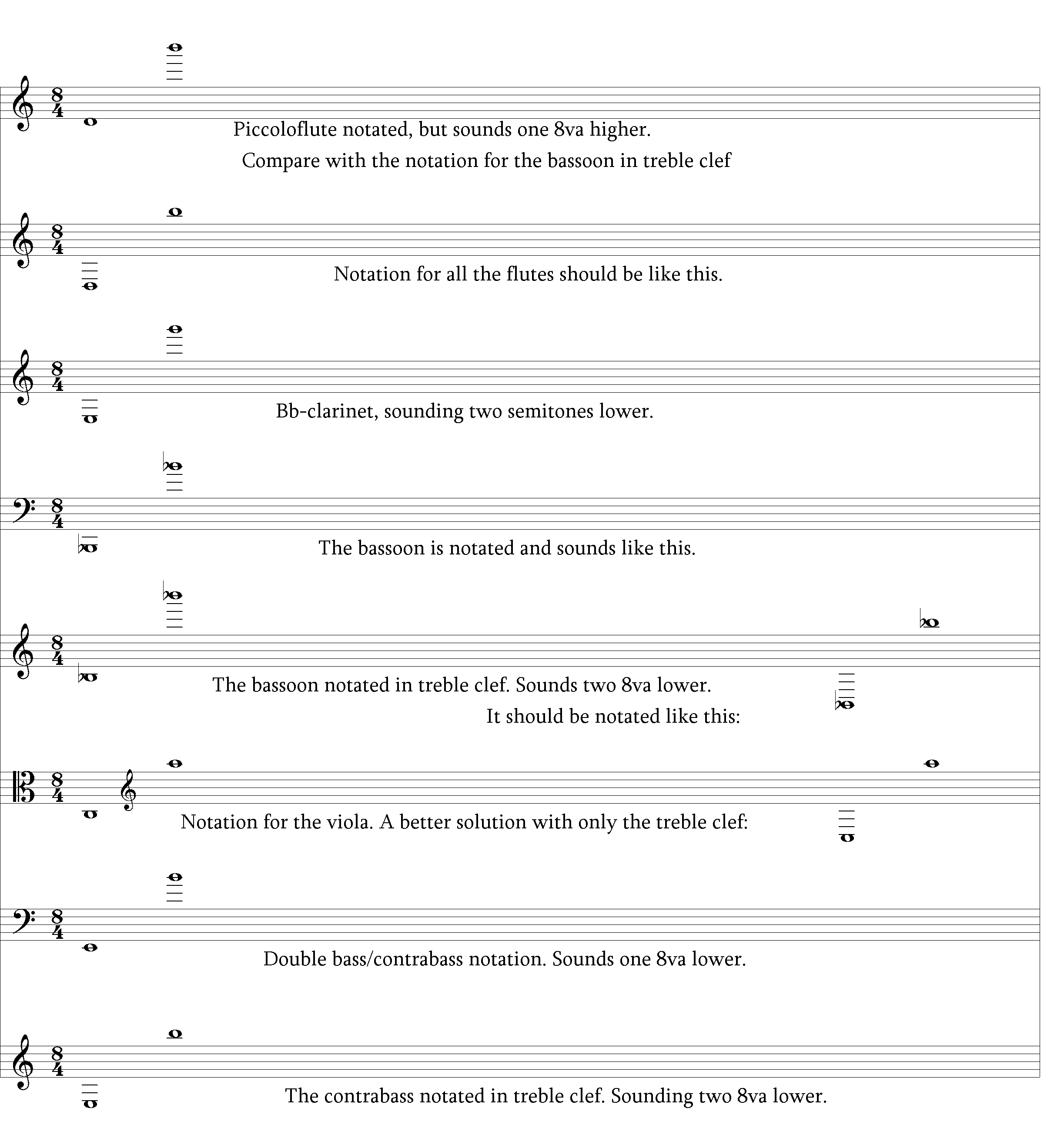

To point out exactly how inconsistent current clef use is, I have a few examples:

- Orchestra bells are notated two octaves too low using the treble clef. In other words, notating too low using the treble clef is okay, but notating too high in the treble clef for the piano, double bass and other instruments is outrageous?

- Americans notate all bass instruments using the bass clef, but in Europe the treble clef is commonly used for Eb-tuba and Bb-tuba. Why not for the piano and the double bass as well?

- The alto saxophone is notated in the treble clef. The viola has almost the same pitch range, but uses both the C-clef and the F-clef on the same sheet music.

- The tenor saxophone sounds lower than the viola, but still uses the treble clef.

We are in debt to the inventor of the saxophones for not using other clefs than the treble clef. The C-clef was earlier in use for brass-band instruments, probably as tenor and alto clefs. Thankfully, this practise has ended. Why? The answer seems obvious.

- Cello players have to read two or even three different clefs. Why not use only the treble clef? If a musician is able to interpret three different clefs, surely he or she can handle a few extra ledger lines, or simply reading an indication of which octave the notes are in.

- Piano players have to read both the treble and bass clef. It will, without a doubt, be a lot easier learning to play the piano if notes are written using only the treble clef. And experienced musicians will have no problem reading this system. See my previous example of piano notes.

- In some books the bassoon is notated using both bass and tenor clef, but the booklet mentioned above uses only the bass clef. Do I sense some progress already?

- When buying sheet music for the bass clarinet, you can choose between notes written in the bass or treble clef. This is very fortunate for me, having played regular clarinet for forty years, since I don’t have to struggle with the bass clef when playing bass clarinet. Why not publish piano notes in the same way? With one old fashioned version and one version using only the treble clef, giving musicians an option there as well.

- When Americans ship sheet music to Europe, they include what they call “world parts.” This is sheet music written in the treble clef for trombones, baritones and tubas. To repeat myself, this should be done for all sheet music, including piano and organ.

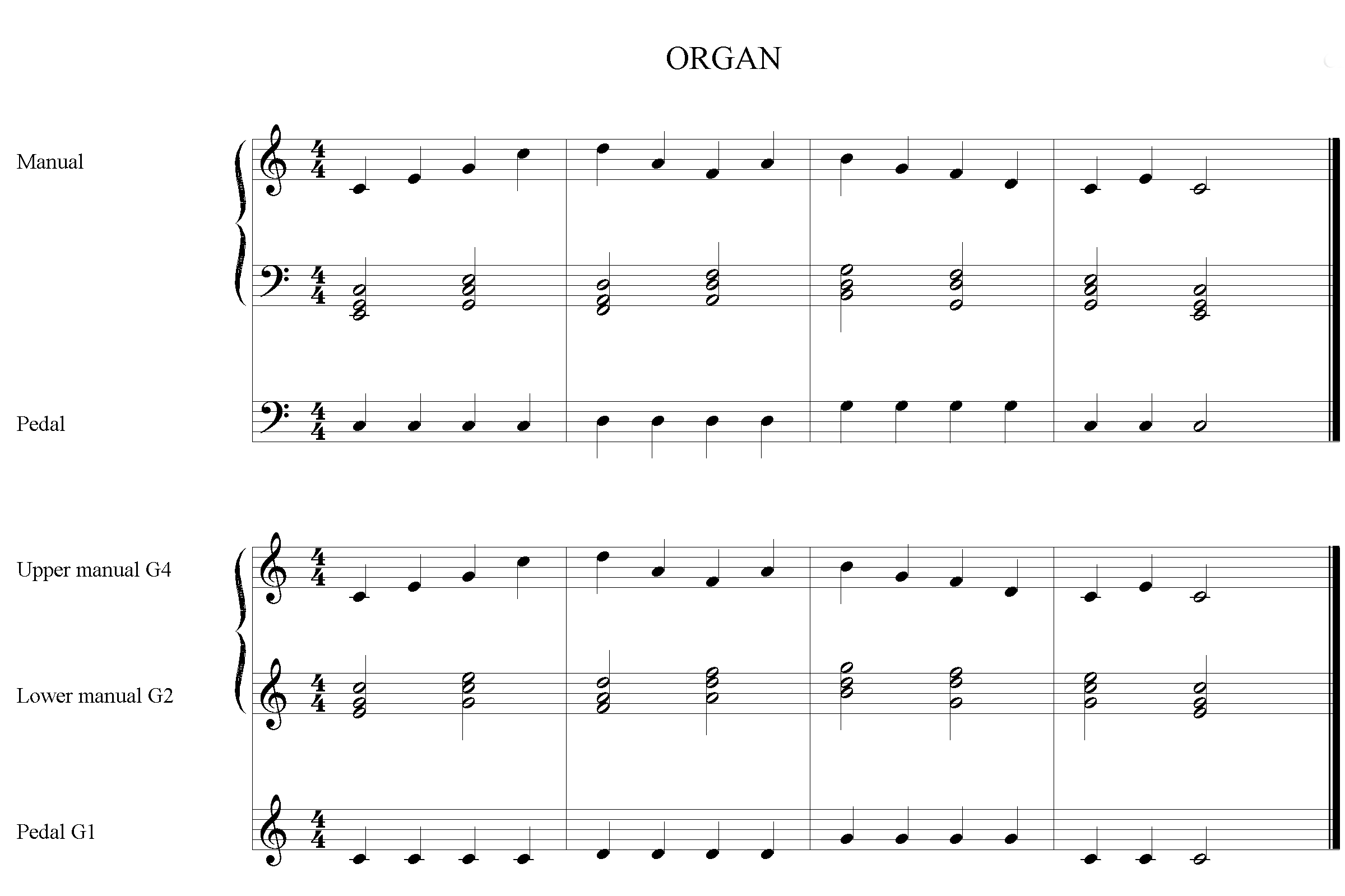

The following overview, called “clef examples”, visualizes that there will be no problems using only a system based on the treble clef.

I would also recommend notating all instruments in such a way that most ledger lines will be placed under the staff. This will help train musicians in sight reading the same ledger lines, which in turn will aid them when playing other instruments. Showing exactly what octave a note is in can be done the same way as in computer programs. Using the standard definition C4 for middle C, adding the number 4 to the G-clef makes it equal to the treble clef, and adding the number 2 to the G-clef makes it into a new, better bass clef.

One single system for music notation will also be a great improvement for brass instrument musicians. With the exception of 4-valve instruments and for French horn, we would only need one fingering chart. Today, six different fingering charts are in use! If you learnt how to play the trumpet in the USA, you won’t be able to play the tuba and sight-read its staff without further training. First, you have to learn the bass clef, and since they call the tuba a C instrument, it also has different fingering.

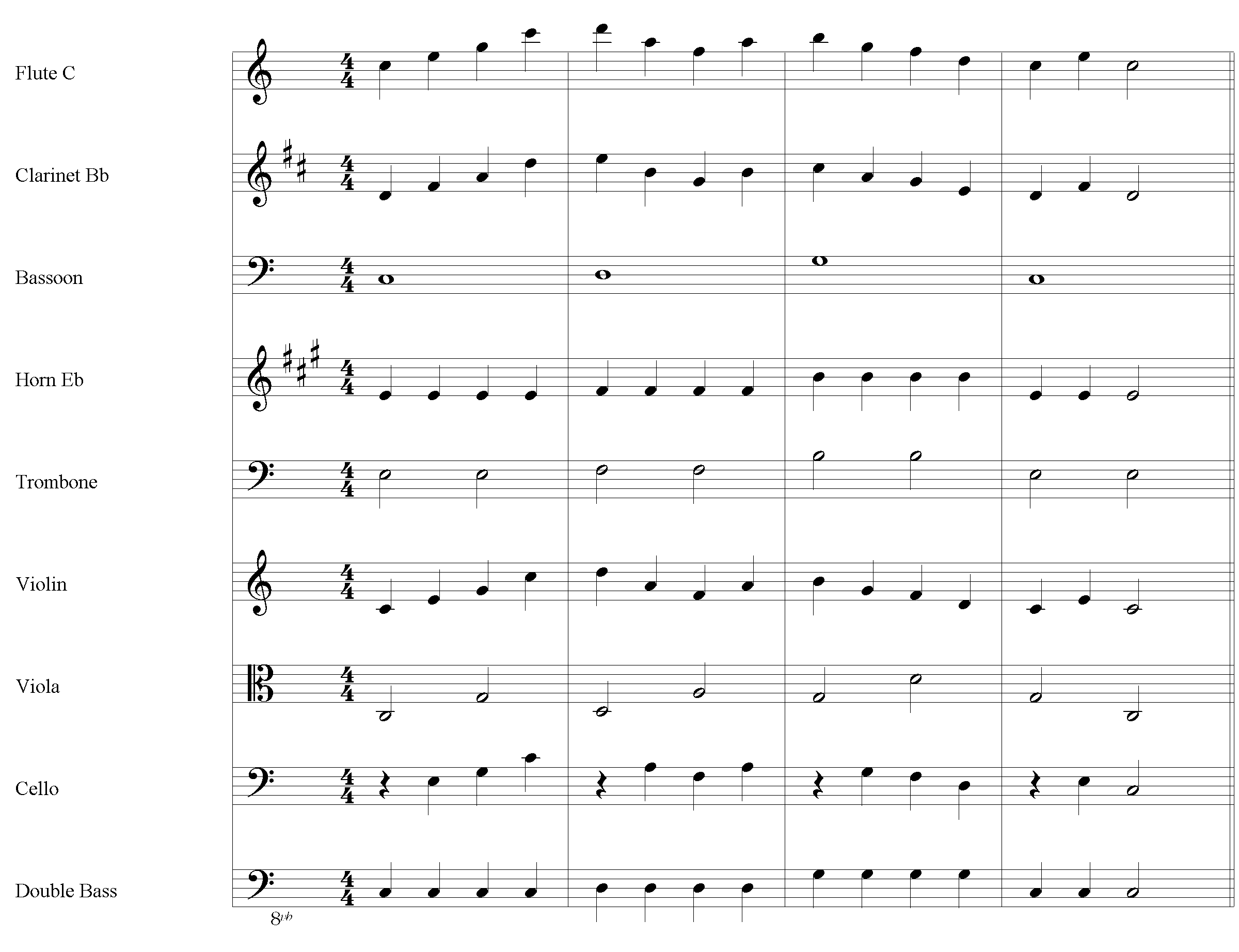

I have made three different scores on the same “melody.” The first score is made the old fashioned way. My “standard orchestra” is far from standard, and is put toghether just to demonstrate several different clefs using only a few staffs. But I guess there could be composed a lot of interesting music for this ensemble.

Standard orchestra

old fashioned score

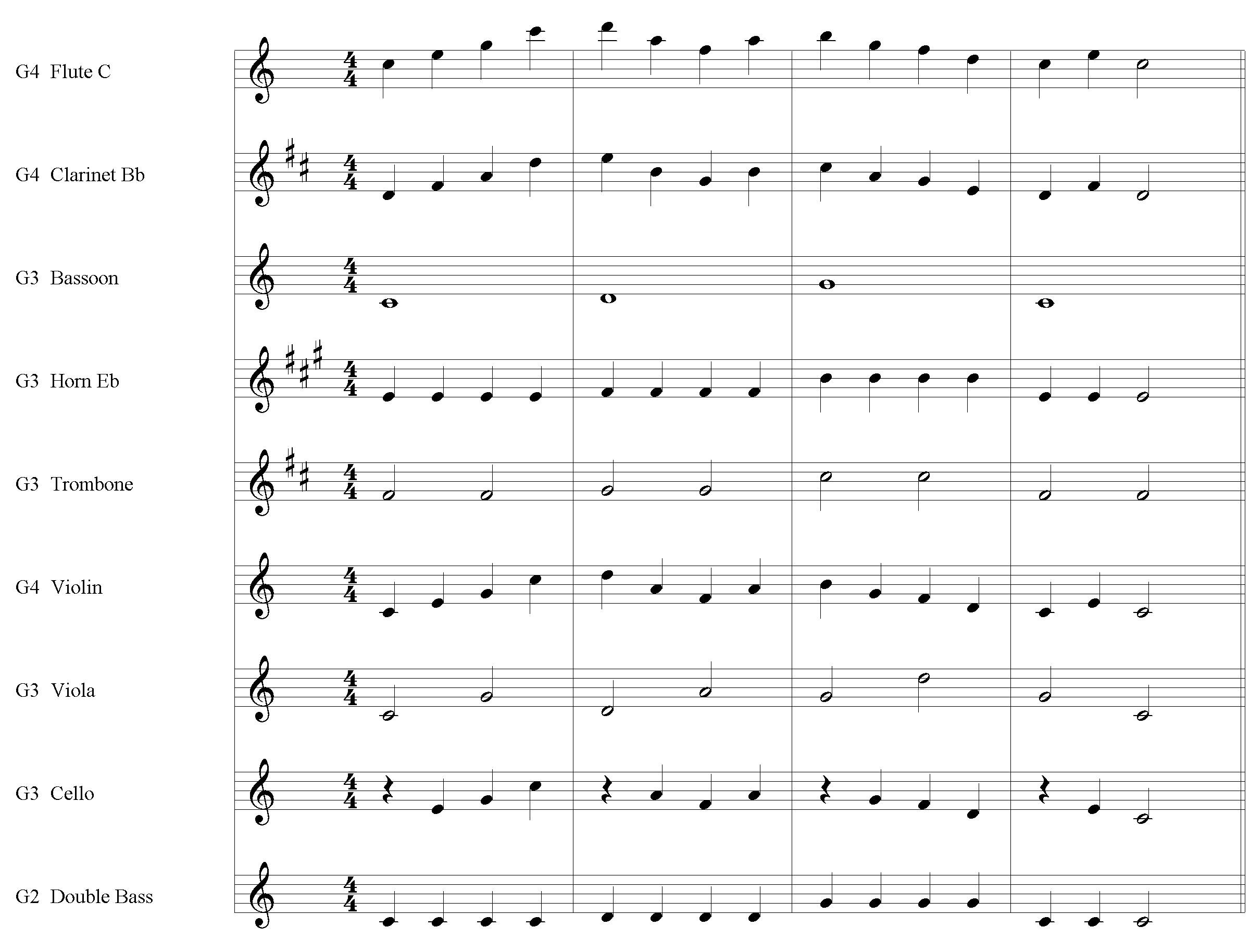

The next score is written to give each instrument notes corresponding to its pitch. And the treble clef is used for all instruments. This is the ideal score. You don’t need many days of education to understand this. If the composer has done his job properly and set his score like the third example, there should be no errors. And a computer can easily transpose everything into the conductor score by a few keypresses.

Standard orchestra

conductor score

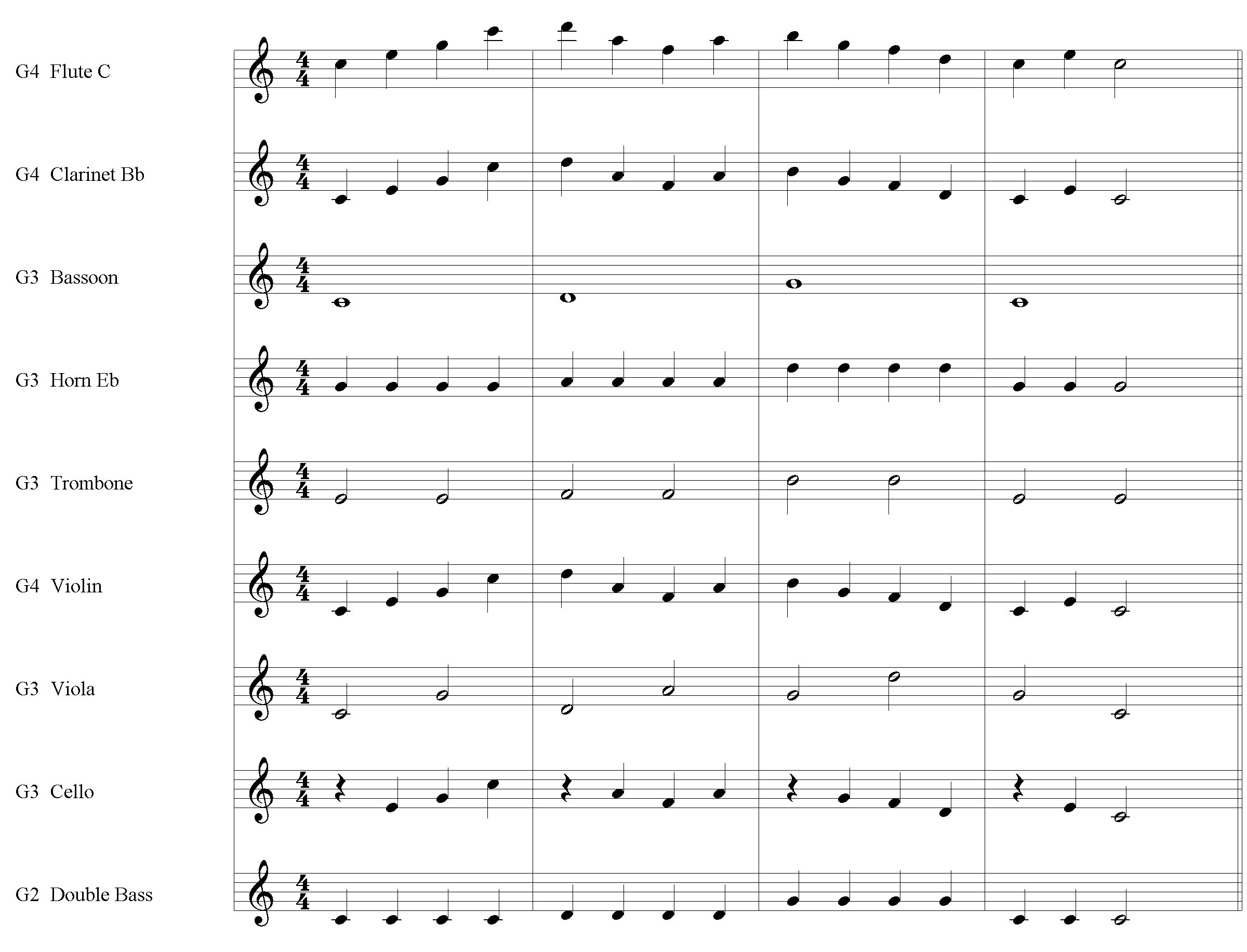

Standard orchestra

composer score

After comparing these three scores, I hope everyone can agree with me that my modern scores are better than the oldfashioned way. Do you disagree? Then I guess you also want to reinstate the old choir scores using both G-, C- and F-clefs? No? Well then, why not drop the bass clef from choir scores as well? As said before; everyone understands that the staffs named bass should be sung by a man with bass voice. The bass clef is not necessarry to explain this. Using different clefs complicates the learning process and confuses singers that haven’t learnt it yet.

Very interesting writing on your part. I will definitely make sure to sign up to your Rss feed so I can be prompted whenever you post again. I’m always on the hunt for unique writers. Be Cool

Thank you for your comment. Nice to see that someone looks for positive things in what they read, and not searching for difficulties and problems. Lot of people agrees with me, but thinks that it is impossible to do something. To all of you reading this; it is the customer who rules the world, if we care, and therefor; ask for music notated without F- and C-clefs. It is a start. If the publishers understand it is a marked, they will produce. chr

This post is going into my bookmarks.

Great approach!

Appreciate your curiosity and questioning in a search for simplicity in music notation.

Keep up the good works! It is possible for one person, or a few, to change the world. It definitely is!